Originally published May 3, 2020

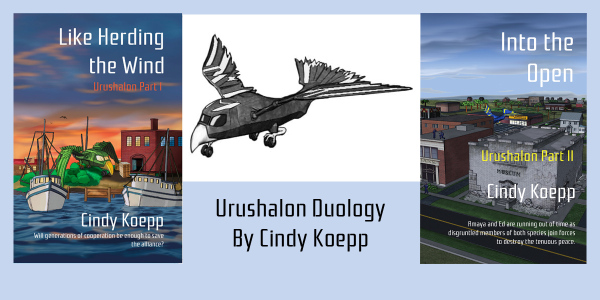

A friend of mine writes scifi/fantasy. I always enjoy her stories and have contributed, in some small ways, to getting some of her titles to market. I love this duology because it focuses on a theme very near to my heart: Can’t we just find a way to get along? Stop by her Amazon page and see what else she is up to.

Here’s Cindy on creating an alternate universe.

After I got the setting for the Urushalon duology nailed down to 1965 in Las Palomas, Texas, I started building the rest of the world and the backstory. The Eshuvani were on their way across the galaxy in a colony ship when something went wildly wrong, and they had to make an almost controlled crash landing on Earth in the 17th century.

They didn’t need long to figure out that Earth didn’t have the resources to repair the ship and that the humans weren’t ready for an alien first contact, so they scattered around the globe and holed up in enclaves to avoid interfering too much with human development.

Fast-forward to 1965 and that policy has bred some mistrust and mutual misunderstandings. The Urushalon duology deals with overcoming those hurdles. When I designed the world, I made the two races similar enough to have common ground but different enough to create sources of tension and conflict.

Physical.

Eshuvani are generally taller and thinner than humans. They came from a lower gravity world, and while adapting to Earth, they’ve developed stronger musculature, but their strength is short-lived. Like an ambush predator, they’re capable of greater speed and strength than a human but only for a short time. In a contest of endurance, humans will win every time.

Emotional.

Eshuvani get waylaid by heavy emotions much more than humans. Humans find them too emotional, but Eshuvani think humans are aloof.

Technological.

Although the Eshuvani colony ship couldn’t be repaired with the resources available on Earth, Eshuvani tech is still way beyond anything the humans have. Medicines that can heal quickly, communication devices that install on the edge of their collars, windows that darken on command, doors that open and close on command, and energy systems that don’t pollute the environment.

Cultural.

After seeing so many conflicts among humans over religion, the Eshuvani converted to the religions most like their own, but their approach is different, which led to a different set of values. They’ve maintained a functional monarchy and a social structure that requires lifetime commitment in many facets of life.

The Urushalon Arrangement

For the Eshuvani, this isn’t exactly their first rodeo. They’ve had first contacts with other races less advanced than they are, but they usually aren’t stuck living on the same planet. Although they don’t want to interfere too much with humanity, isolating themselves entirely will just create more problems in the long run.

To prevent total isolation, individual Eshuvani form a single urushalon relationship with a human. Sometimes they adopt the human, and sometimes the human adopts them. An urushalon is a particularly close friendship. The human gains some privileges in Eshuvani society, as if they’re blood relations of the urushalon. The relationship encourages better understanding between the races.

Hurdles to Getting Along

First Impressions and Other Snap Judgments

When we meet people for the first time, we observe how they dress, how they act, how they move, what they look like, what they sound like, and even the environment we meet them in. All that info collected in mere seconds goes into conclusions about the new people. Those first impressions can stick with us, coloring our opinions even when better information is available.

Those quick judgments can be handy. They can be part of our internal radar that alerts us to potential dangers. Sometimes, though, they’re overzealous and lead us in false directions.

To combat that, realize where the assumptions came from, and when better information is available, be willing to update those assumptions to fit reality.

In Urushalon 2: Into the Open, upon hearing that they’ll have to host a group of humans for a summit meeting, Pavwin, an Eshuvani captain, realizes that the people manning his station have a lot of misconceptions about humans. He asks Amaya, who’s more knowledgeable about humans, to provide better information.

Variations Are Infinite

Stereotyping is one of the major sources of misconceptions and false assumptions. Even within a racial or cultural group, there isn’t just one set of beliefs.

This even occurs in the bird world. I’ve had four cockatiels. Cute little critters, really, but none of them were even close in personality. Sijon was the grumpy old man. Lockheed was a shy sweetheart. Freebie was the social butterfly. Spot was the adrenalin junkie. Sure, they had some similar body language in response to emotions, but the personalities were totally different.

Then I had an African Grey named Masika. Anyone who knows about the red-tailed, gray-feathered parrots has heard about their reputation as expert talkers. They do sound effects and carry on miniature conversations with their humans. Some are even ordering themselves snacks and requesting music from the voice-activated personal assistants. Masika? Not a talker. Sure, she did sound effects and whistled a couple tunes, but only when no one was in the room to watch. Totally atypical African Grey.

In Urushalon 1: Like Herding the Wind, one of the human cops who works for Ed doesn’t like Eshuvani. At all. He has absolutely no use for them, but after meeting Amaya and watching the efforts of her staff to equip, train, and protect the humans, he has a change of heart. Not all Eshuvani are what he assumed them to be.

Do What You Can

No one can do everything but everyone can do something. We each have a part to play in the events we’re involved in. Giving room to someone who’s better at a skill is just as important as being ready to step forward and take the lead in matters we have more skill in. If we all play the part meant for us, we’ll all advance.

In Urushalon 2: Into the Open, Amaya has no experience and very little knowledge of how to interact with the Eshuvani nobility meeting with the human governors at her station, so she relies on Vadin, who grew up within that social level, to provide her with the information she needs. Later, when confronting the source of all their troubles turns into a shoot-out, she uses her superior marksmanship training to protect the others with her. This shows that the situation of her birth does not limit her skill or contribution.

Moving on from Here

We all use information we can quickly gather to make quick decisions about other people. That can be handy in many situations, but it can also get us in trouble because people are unique. Understanding the source of our assumptions can help us avoid Olympic-level conclusion jumping, particularly if we’re prepared to revise our assumptions when better information is available. This will lead to a better understanding of people.

By understanding others, we begin to know what strengths and weaknesses each of us has. We can offer our strengths to support another’s weakness and accept their strengths to support our own weaknesses.

Getting along with others who are very different from us is a skill like any other. Mastery only comes from knowledge and experience.

No Comments