Originally published March 26, 2017

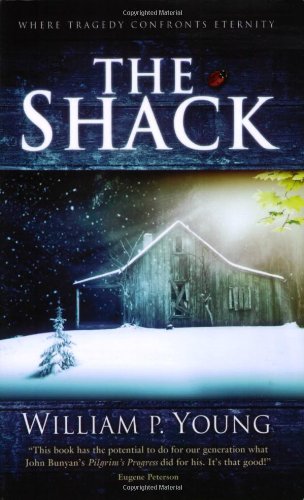

The Shack: Where Tragedy Confronts Eternity, by William Paul Young. Available for $7-18 (movie released this month).

There was such a hullabaloo about the whole thing. There were people excited it was finally going to be on the big screen, as well as people resurrecting the battles over the theology and doctrine portrayed in the original book. As I attempt to do with at least some controversies, I let most of it flow on by. I am, after all, still an avid fan of Oh, God, a movie some evangelicals considered downright blasphemous. I was finally enticed to view the trailer; and I fell instantly in love. I had to have the book, sooner rather than later (and will watch the movie). Every spare moment this week, Kindle in hand, I devoured Young’s tale. Then, I spent a bit of time poking around on the Internet attempting to determine what all the fuss was about. You would have thought the story was a Doctorate Thesis, submitted to the public for vetting. On second thought, maybe it should be. Here is my take on the emotional and spiritual punch, and theological challenge, delivered by this lovely little book.

As a reference point for most of the criticism, I used a fairly prominent Christian blog, www.boundless.org. The article was articulate, and summarized most of the points others were making at various levels of ability and understanding. I found the criticism telling.

First there is the accusation that the story as presented seeks, in many subtle ways, to undermine The Faith. In my opinion, what the author is gently pushing against is the dogmatic doctrine of the church. A structure that believes, somehow, that the interpretations of the early Church Fathers are every bit as holy as the original text penned who knows how many millennia ago. The author points to a particular passage where the character of Jesus states that he is not Christian. Well, as it happens he was not. He was Jewish. Subversion of the “orthodox” view started a couple of millennia ago, I seem to recall the image of Jesus turning over tables in the temple courts.

Since folks like to quote things, let’s look at Proverbs 2:1-5 (ESV). “My son, if you receive my words and treasure up my commandments with you, making your ear attentive to wisdom and inclining your heart to understanding; yes, if you call out for insight and raise your voice for understanding, if you seek it like silver and search for it as for hidden treasures, then you will understand the fear of the Lord and find the knowledge of God.” As far as I can tell, scripture here, and in other places, encourages us to seek insight and understanding—not to accept it as a God-wrapped treasure from those who declare themselves our leaders and sole interpreters of ancient manuscripts.

There is also the issue of how we know God. Many Christians look to scripture as the beginning—and the end—of the discussion. They feel that messages, commands, and admonitions written for people in a different time, different country, and under far different circumstances, should be adhered to without fail today. There are two problems with this approach.

First, it is okay to hold tight to the letter of the law as long as it fits within preconceived notions. Many Christians have problems with the idea of an adulteress being stoned in a Muslim country—and yet that is scripture. Scripture indicates that we should not divorce and that if we do remarry, we are committing adultery. These may sound like old, worn-out arguments, but at the core is this issue: understanding what scripture is trying to impart about the duties of a person that follows the first and foremost command—to love—often comes to blows with modern science, understanding, and culture. The Bible is a living breathing text and should, by all accounts, serve us well whatever the century or however advanced the culture. Look for the message—not the letter—of the law. This is something that The Shack tries to drive home.

And while we’re on the subject, as much as the reader may wish that the Bible was God breathed in every syllable and comma—that is just not a possibility. We do not have access to the original, inspired texts, and we have pushed what we do have through centuries of cultural, personal, and faith driven interpretations. This, of course, is the purpose of the reference to the King James Bible in the book. The challenge to see beyond a specific translation, or interpretation, of scripture and to look for the message that sings the whole way through.

It seems hardly right to devote a short paragraph to the subject of Salvation and what, precisely, it was we see accomplished on the Cross. I keep it short because this is a subject which has been debated since the nascent church began to spread throughout the population of the early Middle East. All the more reason to ponder the thoughts suggested by Young. After centuries of having the hell-fire of sinners pounded into our heads and our souls (a vision we owe more to Dante than the Bible), it is difficult for Christians to see beyond that vision into the conundrum they have created. Simply labeling something a “mystery” is no more than a cop out. We cannot reconcile a loving Creator with an eternal fire—a really eternal fire—for the least of the possible infractions against a code. A code, by the way, we are quick to say was done away with on the cross. If we continue to lock ourselves away in these labyrinths of theological conundrums, we will awaken one day to find we have not done the most important thing we were commanded to do—love. The possibilities discussed by The Shack are thoughts and theories presented by many outstanding scholars within the field. Why would God expect us, no—command us—to forgive whatever the response from the target of our forgiveness—if He was not prepared to do the same?

Oh, and last but certainly not least—how do we portray God? This was a point well brandished in the article I read. According to that author, scripture tells us not to make images of God. Except—scripture does provide images of God and it is those images we defend the most. One is of God as some grandfatherly figure in long robes. And we read that as a white male. When was the last time you saw a portrait of Christ in a church that actually looked like a native of the Middle East? Personally, I was delighted at the portrayal of a functioning, interactive, personification of the multiple aspects of God as defined in scripture—including that of Sophia. I was delighted because that presentation challenges us to break our preconceptions down into the ludicrous assumptions that we defend. Who are we to describe what God would look like as He spoke from the burning bush? Can we really grasp what Daniel, John, or any other author saw in their visions? Would those visions not be based on the people and culture they knew? Do you know without a single doubt, how the Creating force of this universe operates and relates? If The Shack does nothing else—maybe it will break that fragile shell of how we perceive something which we can only grasp in brief and finite thoughts.

Did I agree with everything in the book? Of course not. But I found the story a real attempt to reach people where they are, in the middle of their pain, and carrying years of baggage, some of which they have nothing to do with. One of the most telling bits within the story for me was that Mack never realized that his older daughter blamed herself for the loss of her sister. He was so wrapped up in his own pain, he never thought that someone else may be suffering from the same burden. If you take anything away from this book—know these things. Creation meets us where, and when we are. Our pain is a part of an evolving universe, we are neither the worms beneath our feet, nor lords of the universe. Sharing our pain is how we love one another, and how we help those who also suffer, while healing our own hurt.

Before you attempt to doctrinalize (like that word?) this story into Gahanna—see if you can find some small bit of insight you can work into your own inquiring soul. Or use it to open your eyes to the vast, creative force behind and throughout the universe in which we live.

No Comments