Originally published October 17, 2015

Pleasantville (1998). A classic example of metaphor in art. The standard interpretation of the piece written, produced and directed by Gary Ross is that it was a metaphor of the sixties. America was leaving behind the Father Knows Best and Leave it to Beaver paradigms of the 50s and launching full speed ahead into the sexual revolution and peacenik philosophy of the 60s crowned by such shows as Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In. Okay, I get that. After all, I was there. It was a time when we transitioned from collectively looking the other way when Marilyn Monroe sang happy birthday to the President (May of 1962) to the cultural “freedom” of opening our homes and our bedrooms, to public view—and criticism. Happy Days and Opie consigned to the archives and re-run channels; enter South Park.

There are also the more personal interpretations. Moments of personal change such as when Betty Parker (the quintessential 50s mom) makes the decision to stop hiding the fact she is now in full Technicolor and refuses to use her grayscale makeup to hide it. Or when Mr. Daniels discovers color as an art form and refuses to give it up, even in the face of town statutes. The struggle to seek personal integrity even in the face of prejudice, conflict, and self-doubt.

Watching the movie for the first time in recent weeks, I saw these interpretations; and much more. To me this film was a kaleidoscope of thought provoking moments that went far beyond the superficial presentation of “sexual freedom” and “civil disobedience.” This was most evident in the change brought about in Jennifer/Mary Sue. The most promiscuous individual in the whole story remains stubbornly grayscale until she finds her real passion, literature. Her conversion takes place as she reads from D. H. Lawrence. An author who was considered controversial in the 50s as he confronted many of the underlying themes in the movie. She becomes so impassioned she remains in the Pleasantville universe to attend college. Or, David/Bud remaining grayscale until he ends up in a fight protecting his “mother” from harassment. It was not all about free sex, free speech, and open rebellion. It was about finding that thing which filled the individual with enough passion to become the deliberate vehicle of change.

How then does all of that relate to Nietzsche?

Because Nietzsche had this thing about suffering. Grant it, his view was elitist. He was quite certain that suffering only made sense for those already strong and healthy and was little more than a deep abyss for those who were not. On this I disagree. For a moment, let’s paint Pleasantville with a different brush, one from Nietzsche’s studio.

Pleasantville was the perfect place to live. The greatest emergency was a cat stuck in a tree and no one ever showed up late for dinner or work. The basketball team never lost. No one was jealous, felt left out, or failed at school. It was, quite frankly, what many of us pray for. Unrelenting peace and serenity, no challenges, losses, or regrets. The inhabitants lived in a world so protected that they could not even imagine the thought of “somewhere else.” A condition many practice in real life even if they choose not to admit it. Segue to Nietzsche.

Within a number of Nietzsche’s writings we are introduced to his idea of suffering and what it means in the context of being human. In his view mankind, most particularly those of Christian Europe towards the end of the 19th century, was a mass of sickly worms with visions of greatness, but no capacity to reach it. Though he is saddled with the misnomer of being the father of Nazi philosophy, he would have abhorred the result. In Genealogy of Morals he states, “Do we really need to see in him ‘the spawn of an insane hatred of knowledge, mind and sensuality’ (as someone once argued against me)? A curse on the senses and the mind in one breath of hate?” Although not particularly enamored of the “masses,” he was a man that would have fought against any force that selectively suppressed knowledge, passion, and intellectual freedom on any level.

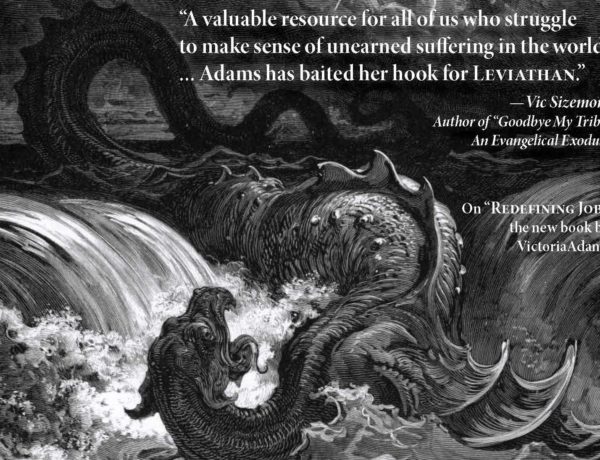

Shall we return to Pleasantville, the land of the perfect and home of the—uninspired? Nietzsche is not, of course, the first philosopher that reserves the true intellectual advance of mankind to some elite group. It is an all too common point of view. In my research for my manuscript on the book of Job I have found many and will, most likely find more. There is, however, a fundamental truth to his perspective. Again from Genealogy of Morals, “but suffering itself was not [man’s] problem, but the fact that there was no answer to the question he screamed, ‘Suffering for what?” We are not afraid of suffering, we are afraid there is no reason.

The lesson of Pleasantville as I see it is that we can choose to paint our lives, our world, and our universe, with the grayscale-brush of protected perfection. Resting in the assurance that the mystery of the why and wherefore is not for us to understand, but to endure. Except—well—we live in a Technicolor universe. If we are to be all that we can be as individuals, as a race, as a representative of what the creative power of life itself can accomplish—we have to accept the consequences of passion. We must embrace the reality of the ever-changing relationship between what was, what is and what will be. Suffering is every bit a part of being human. An essential part that makes us the creators we are.

One of the articles that inspired this post. The Great Conversation – Nietzsche: On Suffering ~ Analysis

3 Comments

Why ban the Giver, by Lois Lowry (1993)? – Victoria's Reading Alcove

June 18, 2023 at 12:48 pm[…] thoughts on why perfect societies are really not all that perfect, you might check out this post on Pleasantville (1998) with a dash of […]

Robert Bridges

July 4, 2024 at 10:22 amand then three Jewish kids went off to the jungle to find an answer to the question of suffering and each, in their own way, own time, own anguish and delight stumbled upon Buddhism. And after each remained in their respective jungles, suffering the heat, the bugs, the sicknesses, the deprivation, the lack of Western 1st world privilege and most of all, went deeply into the jungle and the wildness of their own hearts and minds and found a passion to live for. A passion that made sense of suffering even as the first rule of Buddhism teaches that “Life is suffering.” These three Jewish seekers came home to America and with their hearts opened to the joys of Metta, Karuna, and Mudita (loving kindness, compassion, & empathetic joy) they went about teaching mindfulness of self, other and universe, and changing the world. Jack Kornfield, Susan Salzburg, & Joseph Goldmund……….and the grey people who lived in a black and white world of sin and salvation hated them for reminding them that Jesus taught kindness to self and others, that Jesus lived compassionately with all human beings, and that Jesus danced with joy celebrating the precious moments of life.

alcoveadmin

July 4, 2024 at 12:03 pmBuddhism makes an appearance in my book. I think that finding the core of who we should be is always hard work, and not many are prepared to pursue it. That is why they listen to those who “tickle their ears” and give them formulas that allow them to escape from the demands of a life well lived.