Originally published July 15, 2013:

I posted the first segment of this series on June 9, 2013. The title was A Glimpse from Inside Dementia – Part I and it provided first segment of a talk that I gave. This is the second part of that talk, a piece that I hope will give my readers some understanding of how the mind suffering from dementia handles the concept of time. So here we talk about Time, the biggest abstract of all.

Time is such an elusive concept that even philosophers, neurologists, physicists, cosmologists and mathematicians have difficulty trying to describe exactly what time is. It drives us, eludes us, and holds us captive. Unless, of course, our mind no longer understands just what it is that this thing “time” demands. Some very good resources that describe what we do and do not know about time are Fabric of the Cosmos by Brian Greene (in Book and DVD form) and an episode entitled “Does Time Really Exist” from Through the Wormhole with Morgan Freeman(among others). And yet, with all of the complexity we are discovering about time or space-time, those of us with basic cognitive abilities manage to work within its constraints. Even tribes in the deep of Amazon jungles which have no terms for “time” do have a concept of which season follows which and what activities one does during each of those seasons.

Time as a concept in any form fails almost entirely within the mind affected by dementia. When that happens, an amazing number of anchor points in our lives no longer exist. You might think of a ship at sea suffering from a sudden loss of navigation systems when it’s too cloudy to see the stars.

Losing the “navigation” system of our lives causes a number of issues. For instance, one of the things time does is provide a sequence of events. It provides a logical framework for cause and effect in the activities going on around us. I have included some photographs in this article to better illustrate my point.

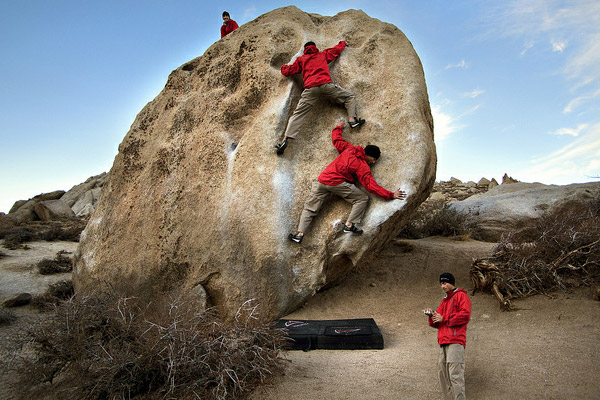

The first one in the series is a sequence of a person climbing on a rock. Looking at the picture, can you tell if the sequence shows the person climbing up or down the rock? Can you be certain of where the sequence begins?

The second photograph shows a sequence of a girl in a swing. Is it evident when the camera first started to record the action? Did the action in the shoot start at the top of her swing to the right, the left? Was she at the bottom of her swing?

This last photo is easier. You can tell what the appropriate sequence is once you look closely enough. However, was it immediately apparent? Did your eye automatically travel from left to right before you stopped and looked closely enough to see the direction the skateboarder was really traveling?

(All photos are examples used by Photoshop to illustrate sequence photography and the use of the program).

For an individual that still retains their cognitive abilities exercises such as these are merely quirks of perception. However, they illustrate a very real problem when discussing the perception of a person with dementia. The inability to correctly identify the order of a sequence of events can have far reaching impacts.

I find that my husband goes from understanding that an event will not take place until later today, tomorrow, or next week, to having no concept of “wait.” Whatever it is must happen right now this minute. Or, knowing that we are going somewhere at 1:00, he’ll be ready to go a 10:00 and will get frustrated at me for waiting so long to leave. Often he decides he is not going at all. This happens with doctor’s appointments where I don’t have a lot of time flexibility. So, I try to schedule as early in the morning as I can. This kind of planning reduces stress on both the care giver and their charge.

Time warping (if you will) also impacts sleep patterns. So far my husband and I have managed well most of the time. I will not get up before 4:00. If he presses the issue I will start his shower and go back to bed. Sometimes he is very apologetic, sometimes we just work through the situation. If you live in an area where the seasons cause a large variation in the daylight hours, it can be even more difficult. I know that sometimes in the far north I will wake up thinking I have overslept and yet it is still “night.” Think of how that works out in a mind no longer able to track time. Occasionally I have a very difficult time convincing him it is still the middle of the night with or without light. I have learned that to some extent I have to let him be up and around. I no longer take it personally if he gets upset because I remain in bed. He will, eventually, get over it.

I mention in my book that I feel that time displacement could be a factor in Sundowning. This is a condition experienced by many folks with dementia which causes them to sleep during the day and be up and wandering around most of the night. I don’t think that is the problem that I currently face. I do feel, however that this, and other types of time disorientation can be mitigated by using routine. Depending on the severity of the situation, routine can conquer a number of issues.

To the best of my ability we do the same or similar things every day, week day or not and we do them at close to the same times and in the same order. I realize that can’t always happen; life doesn’t come in neat packages. However, to the best of your ability, keeping a regular schedule, every day and in a similar order helps a person with dementia develop a set of simple expectations. I notice that when I put things out of order my husband gets terribly confused and works to bring things back to normal. An illustration might help in this instance.

Not so long ago I found it necessary to replace my husband’s file cabinets with something easier for him to operate. He no longer understood that you can only open one drawer at a time. To him, they were broken. After trying a number of solutions to the problem I finally gave up and ordered some storage cabinets with doors. Through the whole process, emptying old cabinets, moving old cabinets, waiting for new cabinets, reloading new cabinets, he was almost constantly agitated. He was so upset over the whole affair that he completely lost his appetite and ended up taking naps a few days.

The real problem came the first day the cabinets were expected. I received a brief, automated message that said my cabinets were late and would be delivered on the 15th. That was the day they were supposed to be delivered. All day on the phone and I never received a firm answer as to whether or not the cabinets would arrive that day. I even fixed dinner before we went to the store so we wouldn’t keep him up too terribly late and so I could still wait to the last possible moment a UPS truck might arrive. They never did. In the meantime the routine had been broken. When we returned from the store, as late as it was, he began setting the table for dinner. It was far easier to fix a bedtime snack than to try to explain that our “routine” had been disturbed and we had already eaten. Habits are life savers and you should try your best to create and maintain them.

Another tool I find useful is calendar counting. Whenever it is obvious that something is important to him I mark it on the calendar and we count each day as it goes by. This method doesn’t solve all issues (such as “no one told me we were going to the dentist then”). It is a way of imposing structure where there is none. As a side note you need to remember that “reminding” a person with dementia that you have told them certain things and have done so a thousand times is counter-productive. It will infuse the situation with emotionally charged reactions that accomplish nothing. I have learned to respond with something like, “Well, someone was supposed to, I will try to find out what happened.”

We talked a bit about sequences of events. There is another aspect to drawing correct conclusions from what you see or think you see and in what order your brain interprets them. I recently watched a program which presented the work of an Associate Professor of Psychology. Donna Rose Addis works at the University of Auckland and her research involves using MRI scans to see how our hippocampus contributes to our ability to construct future events. The hippocampus, you may know, is the seat of our memory. This is the storage room for all the things we know and can recall. What her research has shown is that when we are asked to build a possible scenario about a future event, we rely quite heavily on our past experience.

This all seems reasonable when you think about it. We learn by analogy. We compare new things to the things we know and draw conclusions based on similarities. What happens, though, when the storage room no longer functions adequately? How do you envision a future event if you can no longer track the sequence of events that might lead up to it? Going on a trip to visit your children or relatives in another state doesn’t mean much if the mind can no longer draw reasonably successful comparisons based on previous trips. It’s that time thing again. Losing the grasp of the sequence of life, of what actions cause what outcomes, sets the individual adrift on a cloudy sea without a navigation system. Consider this when your patience wears thin.

I am being asked to publish and expanded version of Who I Am Yesterday. The project will include a re-write of related articles from my blog, some poems, and photos from our week on Vancouver Island; the point it all suddenly changed. Projected release is sometime late this fall. In the meantime, the original can be found on Amazon.com or at the link provided on the page dedicated to the work on this blog. Do you have an experience you would like to share?

This series has one more post in it: the shifting sea of who we are and all those extra people.

2 Comments

A Glimpse from Inside Dementia – Part I – Victoria's Reading Alcove

July 13, 2020 at 11:44 am[…] Who I Am Yesterday is available on Amazon in paperback and Kindle. See you next time with Time, the biggest abstract of all. […]

A Glimpse from Inside Dementia – Part III – Victoria's Reading Alcove

July 13, 2020 at 12:08 pm[…] A Glimpse from Inside Dementia – Part II […]