This past week from November second through the sixth, East Indians around the world have been celebrating Diwali, or the Festival of Lights. The name Diwali is derived from the Sanskrit word, Deepavali, which means “row of clay lamps.” This past year, those in the ancient and holy city of Ayodhya arranged over 600,000 clay pot lamps to honor the festival. Individuals set rows of lamps outside of their homes to symbolize the inner light that protects us from spiritual darkness. The celebration overlaps with the Hindu new year which adds the flavor of renewal and new beginnings.

The festival is celebrated by Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, and Newar Buddhists. Although the primary theme is the triumph of good over evil, each of these groups ties the celebration to a different spiritual or historical event.

For the Hindu, Diwali focuses on the return of Rama and Sita, to Ayodhya, which is believed to be the birthplace of the Hindu god Lord Ram. Diwali is the commemoration of the day he returned home after defeating a demon. The main day of the celebration (November 4 in 2021) is the day set aside for the faithful to pray to the Hindu goddess of wealth, Lakshmi. Diwali ranks high on the celebratory calendar for Hindus, one might compare it to the Christian Christmas.

By Dinesh Korgaokar – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36581728

Sikhs use the festival to honor the day that Guru Hargobind Ji (the Sixth Sikh Guru) was freed from imprisonment in 1619. However, there is evidence that Sikhs celebrated Diwali before this date as the foundation stone of the Golden Temple at Amritsar, the most holy place in Sikh, was laid during Diwali in 1577.

The Jains celebrate the nirvana or spiritual awakening of Lord Mahavira, which records indicate occurred in October of 527 BCE. This was the date of his death believed to have occurred in the town of Pawapuri in the present-day state of Bihar. He was also known as Vardhamana and was the 24th Tifthankara of Jainism. A Tifthankara is a savior and spiritual teacher of the dharma who has achieved a life journey that no longer requires physical rebirth.

Among the Buddhists, only the Newar people of Nepal celebrate Diwali. These people revere a number of deities, some of which are similar to those worshiped by the HIndu and Jain. During Diwali, they offer prayers to Lakshmi and honor the day that emperor Ashoka accepted Buddhism as his faith. He was emperor of a large part of the Indian subcontinent from c. 268 to 232 BCE and, after his conversion to the faith, he promoted the spread of Buddhism throughout Asia.

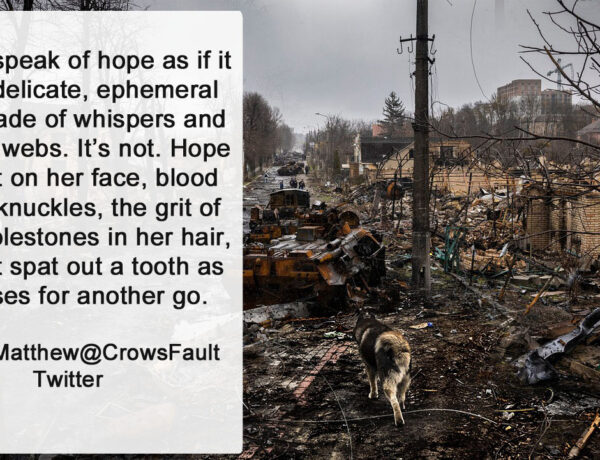

Many of the same traditions are followed around the globe. These include cleaning the house, buying new furnishings, exchanging gifts with loved ones, and buying new kitchen utensils for good fortune. There are traditional dishes, but for the most part, the celebrants simply enjoy good food, sometimes with less meat. Fireworks are a big part and the special candles and lamps are used in public spaces and in front of homes. One aspect that I found intriguing is the use of sand art. I’ve included a photograph of one project, and a video of how the floor sand-paintings are put together. The art is called Rangoli and the designs are varied in style and complexity.

As I tend to see echoes in the varied faith traditions of our species, I wanted to take the time to understand something of the celebratory calendar of those that swirl around us. I love the similarities and the differences. Deep in the heart of the Indian subcontinent, grew a tradition that celebrated light and enlightenment, new beginnings, and renewal of the earth and the lives it supports. Each spiritual tradition that joined the celebration, found a special event to bring clarity and visualization to the underlying message of good overcoming evil.

I do wish to address one last item. The swastika that the west holds with such disdain (well, most of us do) was a horrific appropriation of ancient cultural meanings. In India and within her many faith practices, the swastika is revered. The symbol is meant to represent well-being, prosperity, and luck. Because of that, it’s found everywhere in the subcontinent. The design has roots in the Vedas and its name is derived from the Sanskrit root, swasti which is composed of su (good or well) and asti (it is). The symbol was misappropriated by Hitler due to his certainty regarding the homeland of the Aryan races. Just before the war broke out, Himmler sent a team of five men to search in Tibet for the origin of the Aryan peoples. Hitler believed that the Aryans were punished because they interbred with the local peoples. The confusion will forever confuse and disturb western folks visiting the countries of Asia. Perhaps, this travesty will give us pause when thinking of the impact of appropriation of cultural symbols without understanding or wishing to understand the roots.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this short journey into the a beautiful and ancient tradition celebrating light, goodness, and well-being.

No Comments